“Let the Data Speak for Themselves” is Bad Advice

By Lowell Dempsey, August 5, 2016

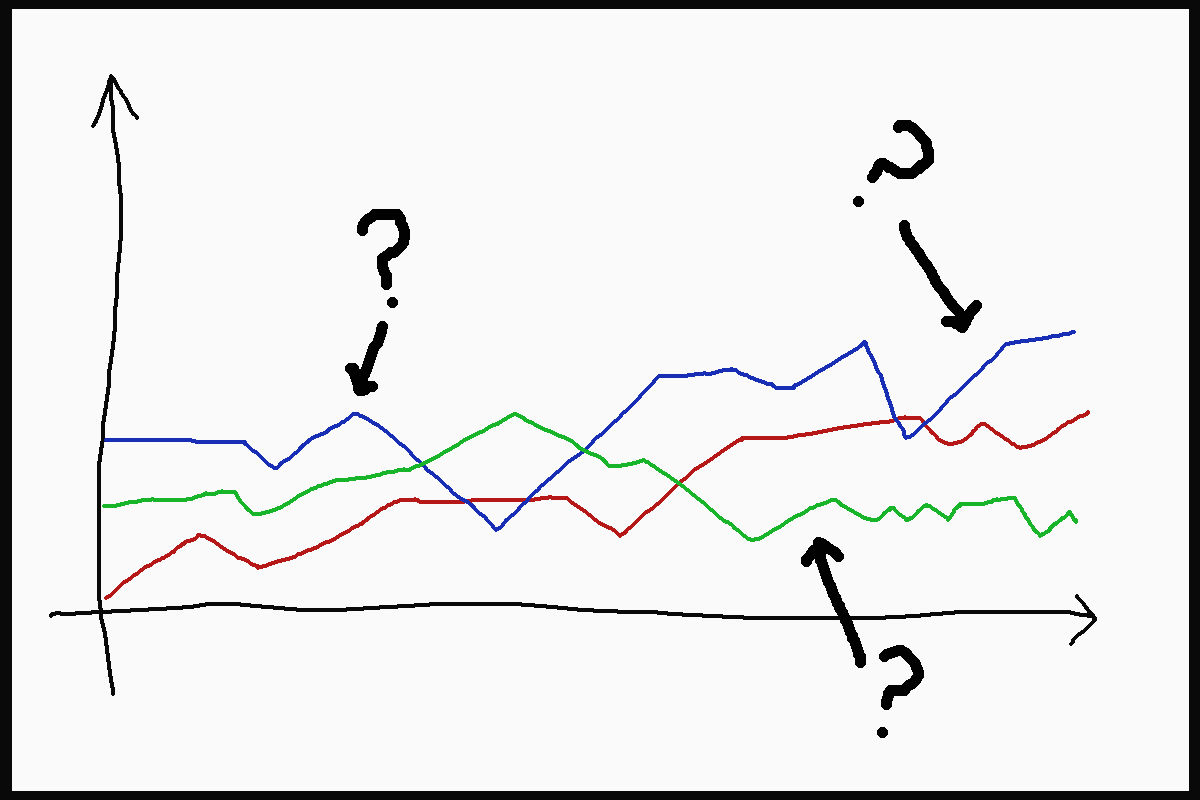

One phrase that I’ve vowed never to use again is “let the data speak for themselves.” Why? They’re really bad at it. When shown alone, data can actually create more questions than answers, particularly if you’re talking about a complex issue like racial disparities in health.

Take the black-white difference in life expectancy, for example – it’s about four years. But what does that mean? With African Americans living to be 75 years old, should we be alarmed because they aren’t living to be 79? Or is there really not that much to worry about because 79 and 75 aren’t that far apart?

The way we understand these numbers could make the difference between proceeding with business as usual or driving a community initiative to improve access to healthcare in black and brown communities, for example.

Statistics without explanation are waiting to be misinterpreted.

No one knows this better than public health researcher and Professor David Williams, whose knowledge we promote through our work with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. His extraordinary and compelling explanation of data has led to multiple forums with media, policy makers, and advocates who are interested in learning more about the link between race and health in our country.

Here’s an example.

Dr. Williams was recently interviewed for a Vox story about race and health. In the interview, Dr. Williams answered a question that has made its way into many mainstream discussions about race: why are so many public health experts, social justice advocates and civil rights leaders directing their attention to the life expectancy of black men and women?

Dr. Williams referenced that same data on the black-white life expectancy gap but framed it with a metaphor to make it real for readers and show them why it matters. Here’s what he said:

One of the ways to think of the racial gap in health is to think of how many black people die prematurely every year who wouldn’t die if there were no racial differences in health. The answer to that from a carefully done [2001] scientific study is 96,800 black people die prematurely every year. Divide it by 365 [days], that’s 265 people dying prematurely every day. Imagine a jumbo jet — with 265 passengers and crew — crashing at Reagan Washington Airport today, and the same thing happening tomorrow and every day next week and every day next month. That’s what we’re talking about when we say there are racial disparities in health.

With just the data and no metaphor, readers might not have been convinced to care about disparities, and they certainly wouldn’t have been able to picture what the data actually meant. But Dr. Williams’ words lend a human element – and urgency – to the issue. In response, the New York Times highlighted the issue on its front page with another quote from David:

“We have had this peculiar indifference to this unprecedented loss of black lives on a massive scale for a very long time. That to me is the big story.”

There are countless examples of this same principle at work, from former Vice President Al Gore’s exclamation to Congress that “the planet has a fever,” to nutrition advocates who point to the consequences of soda and other sugar-sweetened beverages by deeming them “liquid candy.” Data can’t speak for themselves, but with a little help from metaphors and stories, we can paint a fuller picture of the issues we work on, and convince others to care about them, too.